Key Takeaways

Goals Are for Losers. Use systems that allow you to consistently work toward your dreams instead of setting rigid goals. For example, instead of aiming to “lose weight to 70 kg by a specific date,” I’ve been following a system of “working out three times a week” for years (albeit with occasional slip-ups), and it works.

To make money, I break the process down into simple tasks that are most likely to yield results and grind through them daily. For example, I spend a set number of hours each day working on my client pipeline, gathering feedback, and improving the product with clear daily outcomes. The beauty of this system is that I feel like a winner every single day because I complete another small step. Every day becomes a small victory.

And where will you find time for personal life?

If you want to become an excellent product manager, responsible for an interesting product, you will have to grow faster than all the other people who, like you, want to become product managers, and those who are already working as product managers and are also growing quickly. Therefore, you’ll have to sacrifice time for entertainment and personal life. You can’t cut back on rest at all, otherwise, you won’t be able to recover, but there won’t be time left for anything else. Sorry ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Key Takeaways

Goals Are for Losers. Use systems that allow you to consistently work toward your dreams instead of setting rigid goals. For example, instead of aiming to “lose weight to 70 kg by a specific date,” I’ve been following a system of “working out three times a week” for years (albeit with occasional slip-ups), and it works.

To make money, I break the process down into simple tasks that are most likely to yield results and grind through them daily. For example, I spend a set number of hours each day working on my client pipeline, gathering feedback, and improving the product with clear daily outcomes. The beauty of this system is that I feel like a winner every single day because I complete another small step. Every day becomes a small victory.

The main value: The author examines the most fundamental phenomena—life, death, boundaries, power, titles, society, war, culture—and, based on basic axioms, derives more complex concepts.

I grasped, by God, about 70% of the theses and don’t entirely agree with everything. At times, it seems the author oversimplifies and generalizes. BUT perhaps that’s the provocative style—intended to spark reflection rather than to deliver 100% truth. For example, the author claims that society is the essence of finite games and a manifestation of power, described as a collection of rules and norms maintained by force. In my view, this is a significant simplification and selective focus—that is, not a complete description of what society truly is. Considering the book’s goal isn’t to lay out a conventional, exhaustive framework but to provoke thought, it’s acceptable; otherwise, the book would be thousands of pages long.

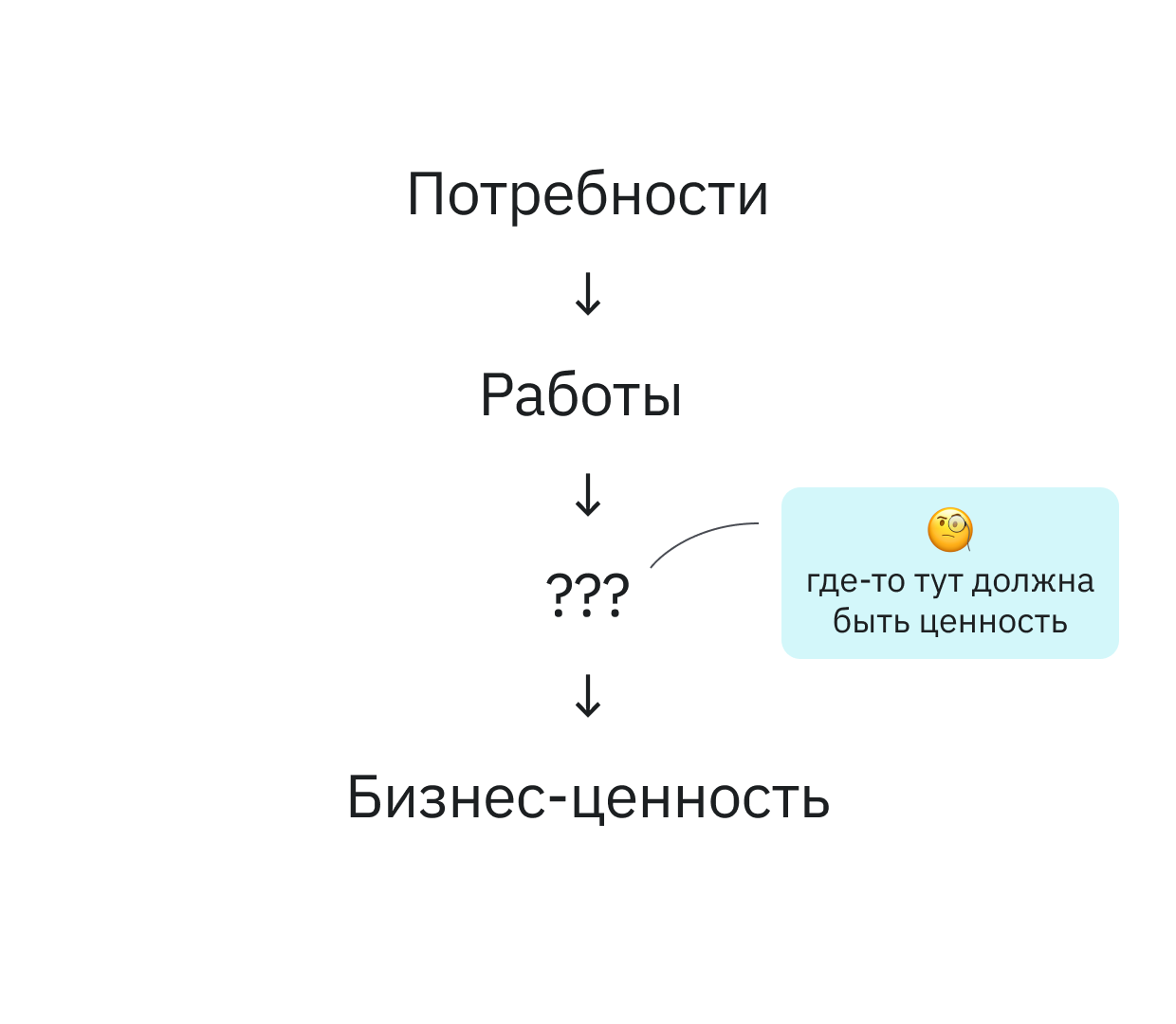

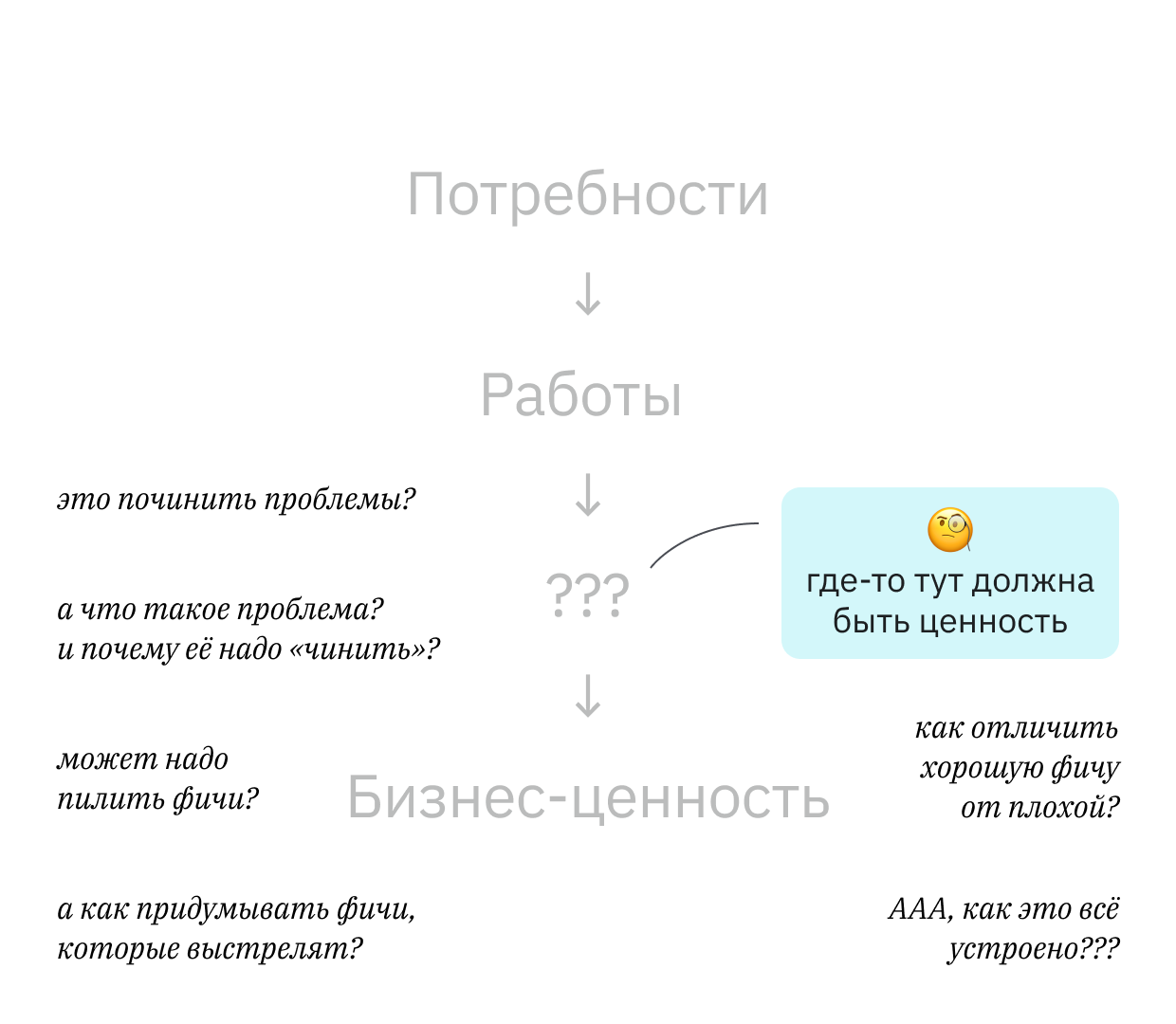

Потребности являются первопричиной любых действий, но большинство людей их не осознают. Мозг формулирует цели, чтобы удовлетворять потребности, и цели уже более-менее осознаются. Цели = работы в AJTBD. Но мы пока что не знаем как сделать так, чтобы клиент купил именно наш продукт. По-идее, важную роль в выборе нашего продукта должна играть роль ценность..

Потребности являются первопричиной любых действий, но большинство людей их не осознают. Мозг формулирует цели, чтобы удовлетворять потребности, и цели уже более-менее осознаются. Цели = работы в AJTBD. Но мы пока что не знаем как сделать так, чтобы клиент купил именно наш продукт. По-идее, важную роль в выборе нашего продукта должна играть роль ценность..

Но у подавляющего большиства людей, которые создают продукты нет понимания как создавать ценность и это вызывает фрустрацию

Но у подавляющего большиства людей, которые создают продукты нет понимания как создавать ценность и это вызывает фрустрацию

Хотя это крайне важный вопрос

Хотя это крайне важный вопрос

Очень многие не знают как устроена причинно-следственная связь, которая приводит к покупке. AJTBD полностью описывает эту причинно-следственную связь и принципы принятия решения человеком и даёт алгоритм создания ценности.

Граф работ

Граф работ—это иерархия работ, которые человек выполняет для того, чтобы удовлетворить свои потребности.

Граф работ—вторая единица [юнит] анализа фреймворка AJTBD и одно из главных отличий от классического JTBD. Первой единицей анализа является работа.

На всякий случай уточню, что «граф»—это математический термин, а не дворянский титул.

Из знания и преобразования графа работ рождается ценность, стратегия продукта, а так же алгоритмы решения бизнес-задач: на какой сегмент запустить новый продукт, как растить конверсии в оплаты, как удерживать и возвращать клиентов, как растить средний чек, как выходить из прямой конкуренции и создавать disruptive продукты и другие задачи.

Я использую термин граф потому что у работ часто встречаются связи многие ко многим, например: работа «нанять компетентного руководителя» может выполняться генеральным директором для того, чтобы выполнить несколько работ выше уровнем: «сохранить сильных сотрудников», «вырастить продажи» и «снять с меня нагрузку».

Реальный граф работ клиента определяется двумя факторами:

- Строением графа работ, которое заложили создатели решения для работы

- Выбором человека выполнить работу с конкретным решением

Именно из этих двух принципов формирования графа работ человека вытекает ценность и стратегия продукта, про это будет позже в этой главе.

Despite the exaggerations, simplifications, and logical flaws, this book remains valuable to me because, while reading it, I spend a long time delving into the very foundations of reality—a rare occurrence with most books.

The book is challenging, filled with paradoxes and contradictions (the author asserts this is a key feature of finite and infinite games), and it’s hard to grasp. It’s short—just 150 pages—but I ended up reading it for about 10 hours in several sittings. Some chapters took me half an hour each, and I still couldn’t fully understand them without the help of ChatGPT.

This isn’t modern non-fiction where everything is spoon-fed with plenty of examples and clear instructions on how to apply it to modern life; it’s philosophy with the stance, “if you need to, you’ll figure it out”—and the book is already 40 years old.

I felt there weren’t enough concrete examples of finite and infinite games in each chapter, but with the help of ChatGPT-o1, I gathered enough examples for myself.

For me, finite games are the games of status—the games and rules of our society. Think of all the sirs, misters, generals, managers. It’s like chess, football, web studio rankings, political elections. Infinite games, on the other hand, are the ever-unfolding evolution of everything before our eyes: scientific progress, art, love, personal development.

Luck can be controlled. Every new skill doubles your chances of success.

I saw in infinite games a common spiritual thesis: “the universe knows itself”—something that is endlessly evolving and becoming more complex—whereas finite games are the games of society, status, and rules. Chaos and order.

Infinite games very much echo one of the main theses of Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity:

"Humanity will always remain at the beginning of infinity in its knowledge."

I have already reread this book three times, and I suspect I’ll reread it many more times.

I hope that someday I’ll be able to fully understand this text.

Theses

I won’t list all the theses, as my goal isn’t to provide a complete summary but to spark your interest.

- There are at least two types of games: Finite and infinite. In a finite game, you play to win. In an infinite game, you play to keep playing.

- Participation is by free choice: A game is born and exists only as long as all participants freely choose to play.

- Finite games are played by fixed rules, have time limits, and only one person can win while the others take their places. During the game, the rules must not change; if they do, it’s a different finite game.

- Infinite games have no time limits—the rules exist solely to allow the game to continue.

- In finite games, players play within the rules and boundaries; in infinite games, players play with the rules and boundaries.

- Finite games are externally limited; infinite games are internally limited.

- In finite games, participants often forget that they freely chose to assume a role in the game and can drop that role at any moment. A woman may identify too seriously as a mother and forget other aspects of her identity. A man may identify too seriously as a policeman and forget that he consciously chose that role—and he is free to exit it at any time. Thus, seriousness is a hallmark of finite games and is linked to roles.

- Surprise is a threat in finite games: Surprise implies a likely loss; astonishing opponents brings you closer to victory. Every finite game player strives to become a Master—possessing complete information so that nothing comes as a surprise, thus maximizing their chance to win. In finite games, surprise is the triumph of the past over the future. In contrast, in infinite games, surprise is both a reward and a reason to continue playing. Without surprises, the game would end.

- In finite games, the past is fixed—rules don’t change, all players’ moves are made, a winner is chosen, and the positions of the remaining participants are set. In infinite games, the past is subject to constant reinterpretation because new knowledge is continually created, allowing us to see the past anew.

- There are finite games (for example, slavery) in which refusal to participate is punished by death, and continued participation means being deprived of freedom. Yet, in this game, there is a contradiction because a person fights for the right to live. Life becomes merely a means to earn the right to live. In finite games where the stake is life, life itself is not part of the game.

- In finite games, death is either a loss (a dead person cannot assume the role of CEO) or a posthumous reward (a monument to unknown soldiers). In infinite games, death is simply part of the game. Players in infinite games play with vulnerability, ready for surprises and even death in the process.

- Infinite games are paradoxical: The players in infinite games wish to continue the game through others. Finite games are contradictory because their very essence is to end the game for oneself.

- Rewards differ: Players of finite games receive titles and statuses that confer power. Players of infinite games have only names. Titles and statuses are bestowed by others, while a name is given at birth. Titles refer to past achievements in games that have already ended.

- Titles and statuses must be accepted by others.

- Participants in finite games play to live [to earn enough money for old age]. “Life only serves as a means of life,” as Karl Marx said. Participants in infinite games live by playing.

- A finite game is a game for life; an infinite game is a game for pleasure.

- Power is visible only in the confrontation of several elements. The element that can move another holds more power. Power is measured in units of comparison—essentially, how much resistance I can overcome relative to others.

- Power is a concept of finite games. To perceive power means to look into the past and acknowledge victories in completed finite games. A person wins not because they have power, but to gain power. If someone possesses enough power, they might not participate in the game at all.

- Evil is the cessation of infinite games imposed from the outside.

- Society is one giant finite game, within which its members play other finite games. Society’s participants can forget that they are free to leave it (for example, a Catholic might forget that they don’t have to be part of the Catholic Church). The power of citizens within society is determined by their ranks in completed or ongoing games. A society’s power depends on its victory over other societies in even larger finite games.

- Power within society strengthens and grows in relation to the society’s overall strength. Citizens’ victories can be safeguarded by the state only if the society as a whole is strong relative to others; hence, citizens concerned with their status and power must work on the unity and constancy of the whole they exist in.

- Culture is an infinite game: it has no boundaries, and anyone can participate at any time.

- “The reason people create society is the preservation of their property.” — John Locke

- Only through self-deception do people admit that they are subject to law.

- Consumption is a deliberate activity aimed at continually convincing onlookers of the indisputable nature of one’s earned title. Consumers show others that they have achieved success by doing nothing. The more one refrains from work, the more they demonstrate—primarily to themselves—that they are the winners of past games.

- Boundaries are the meeting points of opposing forces. Where there is no opposition, there are no boundaries.

- The horizon is a phenomenon of vision. It is the point beyond which we see nothing. The horizon is unattainable. Moving toward the horizon is moving toward the creation of new horizons.

- Every step of an infinite game player is aimed at approaching the horizon. Every step of a finite game player is taken within set boundaries.

- Midway through the book, the author delves into stark metaphysics: love, attraction, poetry, creativity, war, patriotism.